Blood on the Shelves: The High Cost of Palm Oil and the Hidden History of Bananas

Written by Millie Murray

Edited by Sajneet Kaur Mangat

April 19, 2021

This is part of the article-sharing collaboration between The Observer and The McGill International Review.

Gabriel Garcia Marquez was in the business of blurring the lines between the real and the fantastic. In his 1967 novel, One Hundred Years of Solitude, the scene that does so most effectively is the massacre at the train station where the description of 3000 murdered workers shocks the reader out of the little town of Macondo and into the real-world history of the United Fruit Company. The Banana company in the novel “changed the pattern of the rains, accelerated the cycle of harvests and moved the river from where it had always been.” It brought modernity to the Buendia family’s timeless home alongside machetes, murder, and an exploitative colonial relationship that existed then and persists now.

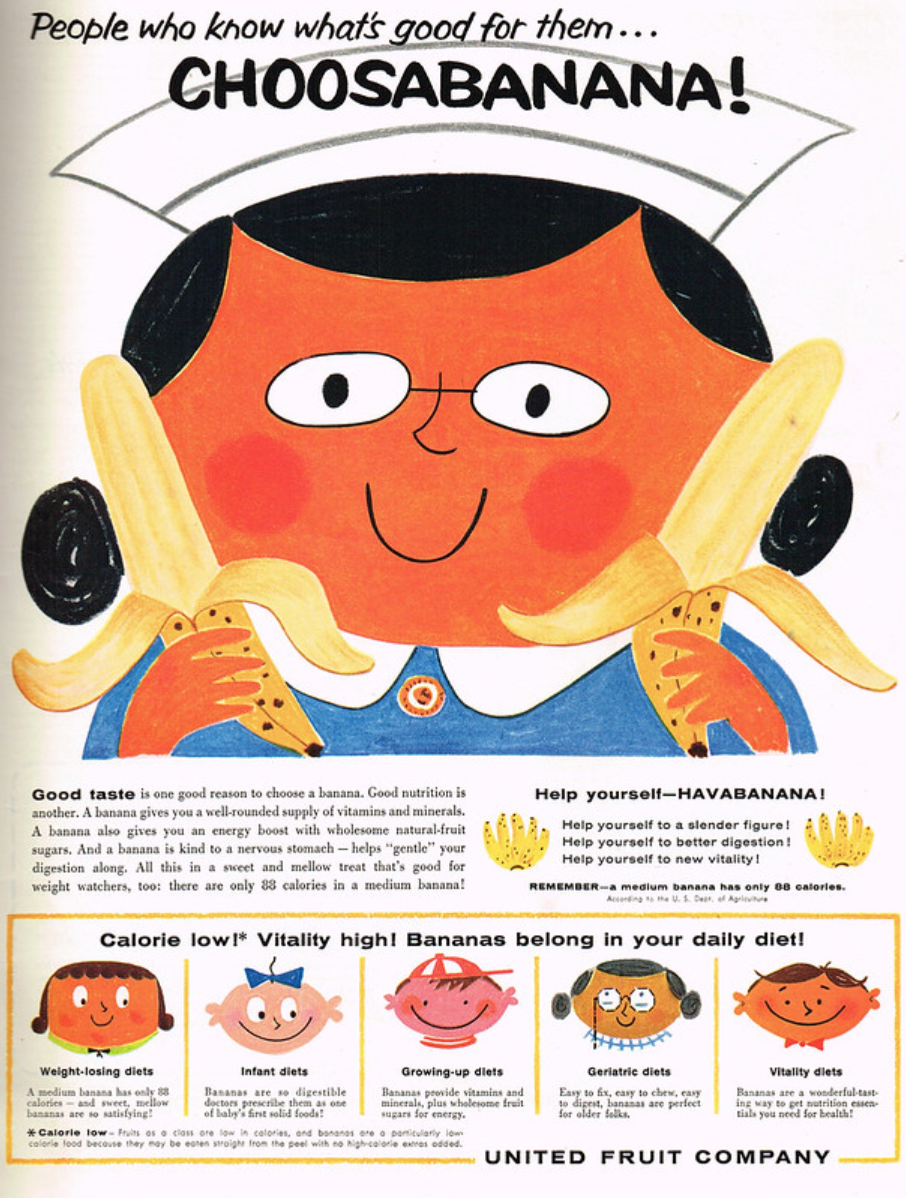

The United Fruit Company, which the Banana Company of the novel is based on, dominated the lucrative banana-growing regions in Latin America for much of the 20th century. The United Fruit Company and their contemporaries’ influence on these areas’ economies and governments gave rise to the term “banana republic,” enough for the United Fruit to be known as “El Pulpo” (the octopus) in Central America. Although bananas are no longer central to corporate calculi in Latin America, relationships enabling exploitation have not disappeared. Today’s colonial resource exploitation masquerades itself in western markets as a healthy alternative to hydrogenated oils and trans fats: palm oil. While palm oil production and banana production are centred in two different places (Southeast Asia and Latin America, respectively), they share a record of human rights abuses and corporate control.

The very bloody history of bananas

The United Fruit Company was formed in 1899 through a merger between Boston Fruit Company and Minor C. Keith. Keith brought bananas to an international audience and established a forceful hold on many Latin American democracies. He, and others like him, saw themselves as heralding modernity to “backward” nations and optimizing “useless jungles“; What they were doing was good and right because they were good and white. A United Fruit executive once stated that Guatemala was “chosen as the site for the company’s earliest development activities because […] its government was the region’s weakest, most corrupt and most pliable”. When the country’s democratically elected president, Jacobo Arbenz, attempted to curtail its power, United Fruit resorted to engineering a coup in 1954 aided by their allies in the American government. The coup opened the door for more than thirty years of military dictatorship and over 200,000 civilian deaths in a devastating civil war.

Colombia suffered at the Company’s hands too. In the winter of 1928, plantation employees in Cienaga went on strike for better working conditions and wages. On December 6, the Colombian military, at the behest of United Fruit, murdered close to 2000 strikers, though the actual number of the dead remains unknown. Marquez’s book alludes to this incident, which is credited by the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, or FARC — a guerrilla group active in the Colombian civil war — with pushing Colombia towards the decades-long political tumult.

In the latter half of the twentieth century, United Fruit lost much of its control as social movements—like the 1959 Cuban revolution and the growth of unions—gained strength in the various banana-growing regions in Latin America. Nonetheless, the company still exists as Chiquita Brands International, controlling about 14 per cent of the global banana trade. In 2018 a Colombian court charged Chiquita Brands for funding paramilitary death squads during Colombia’s 52-year conflict and as recently as 2004. A rose by any other name would smell as sweet, and it seems that a banana company by any other name will continue to exploit the Global South for-profit violently.

A modern take on an enduring relationship

The new star product in resource exploitation is palm oil, but a change of scenery has not drastically altered the relationships of corporations, land, and workers. Palm oil, it seems, is in everything. According to the World Wildlife Fund, more than 50 per cent of products on US supermarket shelves contain it. The palm oil boom (palm oil import to the US grew by 446 per cent) follows the National Academy of Sciences’ 2002 publication warning against the ill effects of trans fats and subsequent move away from hydrogenated oils. Around 85 per cent of palm oil imports come from Malaysia and Indonesia. As a result, the economies of both nations have expanded, but at the costs of catastrophic greenhouse gas emission levels, species extinction, and some of the highest deforestation rates in the world.

The environmental effects of palm oil are massive, but the human rights abuses most clearly call the legacy of United Fruit to mind. In June 2016, Malaysian environmental activist Bill Kayong was murdered by Stephen Lee, head of the palm oil company Tung Huat, and his assistant. Relationships between corporations and the Global South constitute a neo-colonialism where foreign conglomerates, like Singaporean Tung Huat, capitalize on lax labour laws, low wage policies, and resource extraction to maximize profit. Massive corporations, like Nestle, are invested in maintaining child labour and the suppression of activists to keep supply chains open and products cheap. Wilmar International, which controls about 43 per cent of the global palm oil trade, actively exploits forced labour and child labour on its Indonesian plantations. The age of employment in Indonesia is 15, but on plantations owned by Wilmar and other companies, children as young as eight are given the same backbreaking labour as their parents. The complex system of wage calculations and casual work arrangements make the workers vulnerable to exploitative practices, all for manufacturing North American consumer goods.

While Indonesia and Malaysia may be the center of the global palm oil trade, palm oil production in Latin America is almost indistinguishable from the past banana plantations. In 2009, a military coup, allegedly backed by the US government, removed the Honduran President Manuel Zelaya when he facilitated negotiations between palm oil producers and farmers. The new military government has since been busy cracking down on campesinos (peasant farmers) and their advocates fighting for land rights in the palm-oil-producing northern region. In 2012, Honduran human rights lawyer Antonio Trejo was murdered at a wedding. At the time of his death, Trejo represented campesinos in Bajo Aguan in Northeast Honduras against palm-oil producers. Between the 2009 military coup and Zelaya’s death in 2015, there were widespread reports that Honduran palm oil magnate Miguel Facussé had ordered the murders of over one hundred campesinos and defenders such as Trejo. Unsurprisingly, Facussé was also allegedly involved in the coup.

Republic of exploitation

The relationship between palm oil and bananas isn’t direct; the United Fruit Company did not abandon bananas for palm oil and export their tricks to Southeast Asia. While the palm oil plantations in Latin America are the most obvious inheritors of “banana republics,” the legacy of United Fruit and its previous stranglehold on Latin America can be seen in the growing control that corporate giants like Wilmar have in Indonesia and Malaysia. If one were to co-opt a poem, they might say that ‘there are strange things done in the midnight sun by the men who moil for gold, or in this case bananas. But it seems that the residents of Marquez’s Macondo said it best: “Look at the mess we’ve got ourselves into just because we invited a gringo to eat some bananas.” United Fruit Company was the Gringo that took bananas and made itself an empire built on blood and exploitation. As the barons of the Banana Republic lost their grip over the twentieth century, palm-oil tycoons filled their empty shoes profiting from abuse, murder, and the exploitation of the global south.

--This article was originally published by McGill International Review on March 22, 2021. This article is a part of the an article-sharing collaboration with McGill International Review, a Print and Online publication from McGill University.--

Marquez, Gabriel Garcia. Cien Años de Soledad. 1967. Chapters 12-14.